Ebola Today: A worsening crisis in Sierra Leone

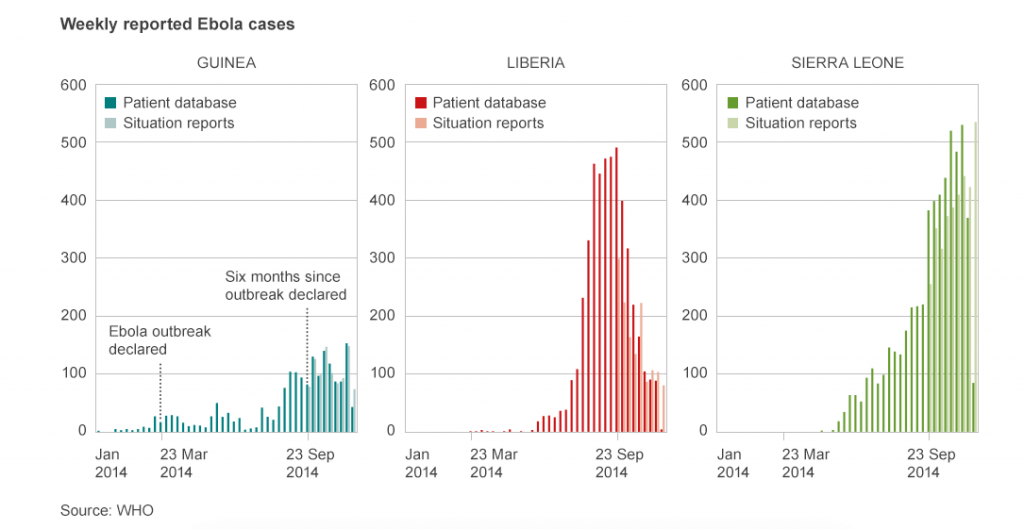

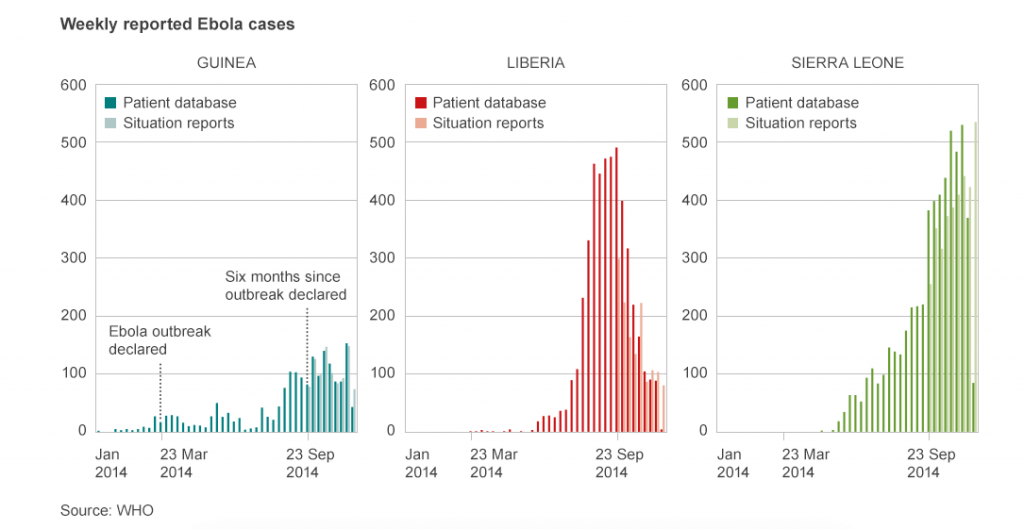

Graph taken from BBC article “Ebola: Mapping the Outbreak”[1]

The above shows that the weekly reported Ebola cases in both Guinea and Liberia are declining, and have been since the beginning of September. However, despite these countries’ ability to control the outbreak, the cases in Sierra Leone’s are still rising.

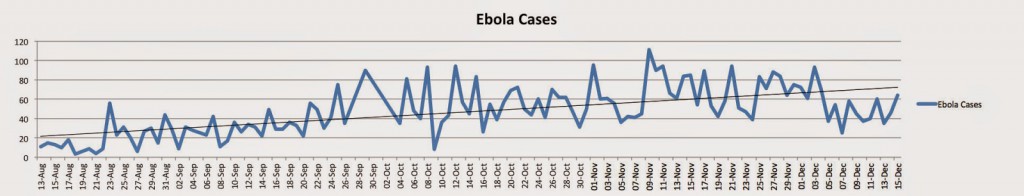

Worryingly, the number of cases per day has more than tripled since early August. It is worth noting that these statistics have been widely criticised for under-reporting the new cases yet the total number of cases now reaches over 6000 in Sierra Leone even according to these figures. The mean growth shows a very clear increasing trend with little sign of slowing.

Without speed and effective measures, he says that Ebola could become a permanent disease in that part of the continent.

This is a worrying statistic. Why has the international response been so ineffective in isolating and paralysing the disease in Sierra Leone? Well, there are a number of factors.

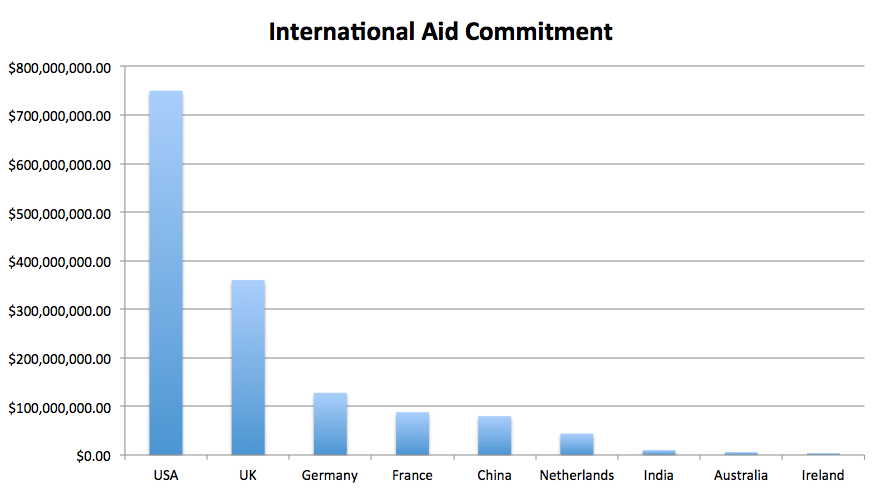

It was widely documented that aid from the international community was slow to arrive, particularly from those countries with colonial ties to the suffering countries: UK with Sierra Leone, USA with Liberia, and France with Guinea. It is undeniable that the lack of assertive early action has allowed the virus a head start on the aid community.

Having said that, the international response following the slow start has been strong, particularly from the former two of those aforementioned countries.

Considering this influx of aid, why have these organisations been ineffective in the targeted delivery of their objective: to slow and stop the spread of Ebola?

An open letter sent to Justine Greening, the international development secretary, signed by 53 doctors, charity representatives and a former British diplomat, have warned that the UK must step up efforts to contain Ebola in Sierra Leone. The letter goes on to say that it is necessary to avoid a catastrophic loss of life that may well lead to a situation where the “health services will collapse entirely”, resulting in a “public health disaster that will eclipse the Ebola outbreak itself and provide the perfect incubator for further outbreaks”.

In an article on the letter, the Guardian notes that the signatories pick out access to Sierra Leone as a major issue. They say that measures such as the UK’s department of transport revoking Gambia Bird’s permit to fly direct from London to Freetown has prevented them from deploying the “significant resources” that they have already amassed.

The signatories praised the British decision to build large hospitals in permanent structures and intrinsically considering the longer-term future of the country. However, it noted that the first of six DFID-funded hospitals, which opened in the beginning of November, will not be fully operational until January. The remainder have yet to even open.

“The deployment of low-tech treatment centres in local areas is the only way to achieve the rapid scale of capacity required,” said the letter.

According to the CIA World Factbook, Sierra Leone had only 120 doctors for 6 million people at the beginning of the Ebola outbreak; that’s 1 doctor for every 50,000.

The packed conditions, under-resourced care centres, and lack of trained healthcare staff means that the existing staff must work longer and harder every day. The exhaustion that sets in leads to mistakes, and Ebola mistakes are, more often than not, deadly. Ebola has already taken the lives of 10 doctors to date. It has also infected 125 health workers, and killed 91 of them. Despite apparently not receiving their ‘hazard pay’, they are taking extraordinary risks on a daily basis. This has been of such concern to the international community that it has been deemed necessary to set up aid programs exclusively to help the healthcare volunteers of Ebola.

Returning to the points raised by Dr. Frieden and the open letter signatories, there is a very clear message: the ability paralyse the virus is dependent on the quick identification and isolation of sufferers in multiple locations around the country. Whilst the big hospitals and care centres will be able to handle and treat those sufferers, the key element is segregating those who are sick before they have time to pass on the virus to those who are not, and this needs to be done firstly on a local and regional level.

It is my belief that this posits organisations such as EducAid in a pivotal position. Organisations like ours have the capacity, the human resource, and the vested interest in Sierra Leone to assist the larger organisations in the isolation of Ebola. For example, Phase 3 of our #AfterEbola programme is already taking in the lowest risk Ebola orphans. With the appropriate medical partnerships, and programmes agreed by government and international organisations, we would be in the perfect position to accept a broader set of at-risk orphans and to isolate any of those showing signs of Ebola.

Not only are we an organisation that can help in the short to mid-term by providing buildings, human resources, and other infrastructure, but we are an organisation that will continue this care in to the long term and be able to provide a seamless transition in to on-going stable education, care, and a future for these vulnerable children.

We are not simply talking the talk; we have begun to engage the communities in our #AfterEbola Phase 3 projects, and we’ve received countless applications from communities who need help with the number of orphans that they have. We have ensured that our buildings are prepared, our staff are trained, and our students ready to begin accepting those orphans in to our Phase 3 programmes – this has taken time, effort, and money, but there is always more to do.

Simultaneously, we are continuing Phase 2 of our #AfterEbola programme in educating those of our students who have not been able to return to our schools by way of Podcasts distributed on MP3 players, on WhatsApp and via BlueTooth. This is particularly important because we fear that those who lose touch with EducAid and their education over this period may never return. Our focus is to bring these students back and ensure that we continue with all of the hard work that they have put in so far.

We really need your help. All of the costs associated with these programmes: mp3 players, recording equipment, building materials, the spiralling cost of food, anti-malarial prophylaxis, additional hygiene and sanitation measures to keep our students healthy, as well as responding to calls to go into the communities are all an expensive process.

They are expensive, but they are absolutely necessary. We are trying to forge a progressive path to securing Sierra Leone’s future. Anything that you can spare as a donation this Christmas time is appreciated.

We rely heavily on the generosity of our donors, and we know that we have your support when it really counts.

Now is one of those times.

Please support our fight by clicking here.

[1] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-28755033